[ad_1]

The Dazzling New Loans in the Armor Court

By Amanda Mikolic, Curatorial Assistant for the Department of Medieval Art

Now on view in the Armor Court are four suits of armor made for members of the Habsburg family, currently on loan from the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna through 2024.

The House of Habsburg was the dominating royal house in Europe for centuries; kings of Bohemia (part of the Czech Republic today), England, Germany, Hungary, Croatia, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain came from this line. Further, the throne of the Holy Roman Empire was in the hands of the Habsburgs from 1438 through 1740.

The house takes its name from Habsburg Castle, a fortress built around 1020 in Switzerland by Count Radbot of Klettgau. His grandson, Otto II (1096–1111), was the first to take the name Habsburg as his own. They gained power through dynastic marriages, ruling most of central Europe, Spain, Belgium, and parts of Italy for nearly 600 years between the 1400s and 1900s. Perhaps lesser known was that they were passionate collectors and generous patrons of the arts. Via inheritance, the Habsburgs were the recipients of objects from very diverse lands. Their art collection was scattered throughout Austria until Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916) built the Kunsthistorisches Museum to provide a suitable setting for their formidable holdings, opening around 1891. The collection numbers among the finest of its kind and is the best-documented collection of court arms and armor in the Western world.

One of the most famous members of the Habsburg family is Maximilian I (1459–1519), German Roman emperor. Maximilian was named after an obscure saint his father, Frederick III, believed had sent him a message in a dream. He was a supporter of the arts and sciences and surrounded himself with great scholars; his reign saw the first flourishing of the Renaissance in Germany. He commissioned many great works by artists such as Albrecht Dürer and was a great enthusiast of knightly skills, hunting, tournaments, and armor as an art form. He sponsored some of the most extravagant tournaments of his era and was a noted patron of fine armor. Maximilian posed the following question: “What could be more precious to a king than an armor that will safeguard his body in combat?” This suit commissioned by him was likely made for the festivities surrounding his coronation as king of the Romans in 1486 (figure 1).

Maximilian’s son, Philip I of Castile (1478–1506), also called the Handsome or the Fair, was Duke of Burgundy from 1482 to 1506. Through the death of his mother, Mary of Burgundy, he inherited the greater part of the duchy of Burgundy in Franceat age four. Although Philip was heir to the Holy Roman Empire, he never took the throne due to his untimely death at age 28. This suit of armor is one of several that were ordered by his father in 1494. The commissions, made for the tournaments that accompanied the festivities of Maximilian’s wedding to Bianca Maria Sforza, were carried out jointly by brothers Lorenz Helmschmied (1445–1516) and Jörg Helmschmied the Younger (d. 1502). The Helmschmieds from Augsburg were one of Europe’s foremost families of armorers, sought after by kings, emperors, and other wealthy nobility. Philip I was 16 when he wore this armor to participate in the games (figure 2).

With each successive generation, the collection of the Habsburg family grew to include works of art and armor from other powerful families across Europe. Philip I’s grandson, Archduke Ferdinand II of Austra (1529–1595), was a great collector. At Ambras Castle near Innsbruck, he assembled a magnificent collection of ceremonial suits of armor and weapons that had belonged to famous princes and military commanders all over Europe. Immensely proud of his collection — known as the Heldenrüstkammer, or Armory of Heroes — he published it multiple times in a book titled Armamentarium Heroicum, or The Heroic Arsenal. This included a suit of armor worn by his brother-in-law, Alfonso II d’Este (1533–1597), who had married his sister, Barbara of Austria, in 1565 (figure 3).

Alfonso II d’Este was the last Duke of Ferrara and grandson of Louis XII of France and Anne of Brittany. He fought in the service of Henry II of France against the Habsburgs. Although he married three times, he produced no heirs, which led to the loss of his kingdom to the Papal States by Pope Clement VIII, on the grounds that there was no legitimate heir. Although he is credited with bringing Ferrara to its greatest height, his family was forced to leave the city. A great lover of the arts and sciences, Alfonso was a friend of Galileo Galilei’s and passionate about poetry and music, especially castrato singing, a type produced by the castration of a male singer as a boy before his larynx changed. This exceptional armor was commissioned when Alfonso was a young man and was likely for a special occasion (figure 4).

A generation later, Andreas von Österreich (1558–1600), also known as Margrave Andrew of Burgau, grew up with his younger brother, Karl, in Bresnitz Castle in Bohemia and later at Ambras Castle. Their father, Ferdinand II, married Philippine Welser, who was from a wealthy family of merchants and financiers and as such was considered inferior to royalty. As a result, Andreas and Karl were not recognized and were unable to inherit lands from the Habsburg dynasty. Instead, Andreas entered the clergy and became a cardinal at age 17 and, later in life, ascended to the positions of abbot, bishop, and governor-general. This suit was made for Andreas when he was ten years old (figure 5).

Although its function was to be protective, richly decorated armor was a symbol of status and a significant investment of time and money. As such, suits were included among the great treasures collected by the Habsburg family and passed down through the generations until the creation of the Kunsthistorisches Museum. We are thankful to the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Foundation for its generous support of these loans.

Image Citations

Figure 1

Maximilian I, c. 1500. Bernhard Strigel (German, 1460–1528). Oil on wood; 60.7 x 40.9 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Inv. R. GG_922

Jousting Armor (Stechzeug) of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519), c. 1485 Workshop of Lorenz Helmschmied (German, active Augsburg 1477–1515). Steel and leather. Lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna, Inv. S VI

Figure 2

Philip I, c. 1500. Master of the Legend of the Magdalen (Flemish, active c. 1490–c. 1526). Oil on wood; 31.1 x 20.3 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Inv. Nr. 4449

Jousting Armor (Rennzeug) of King Philip I of Castile (1478–1506), c. 1494. Workshop of Lorenz Helmschmied (German, active Augsburg 1477–1515). Steel, leather, wood, and brass. Lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna, Inv. RII

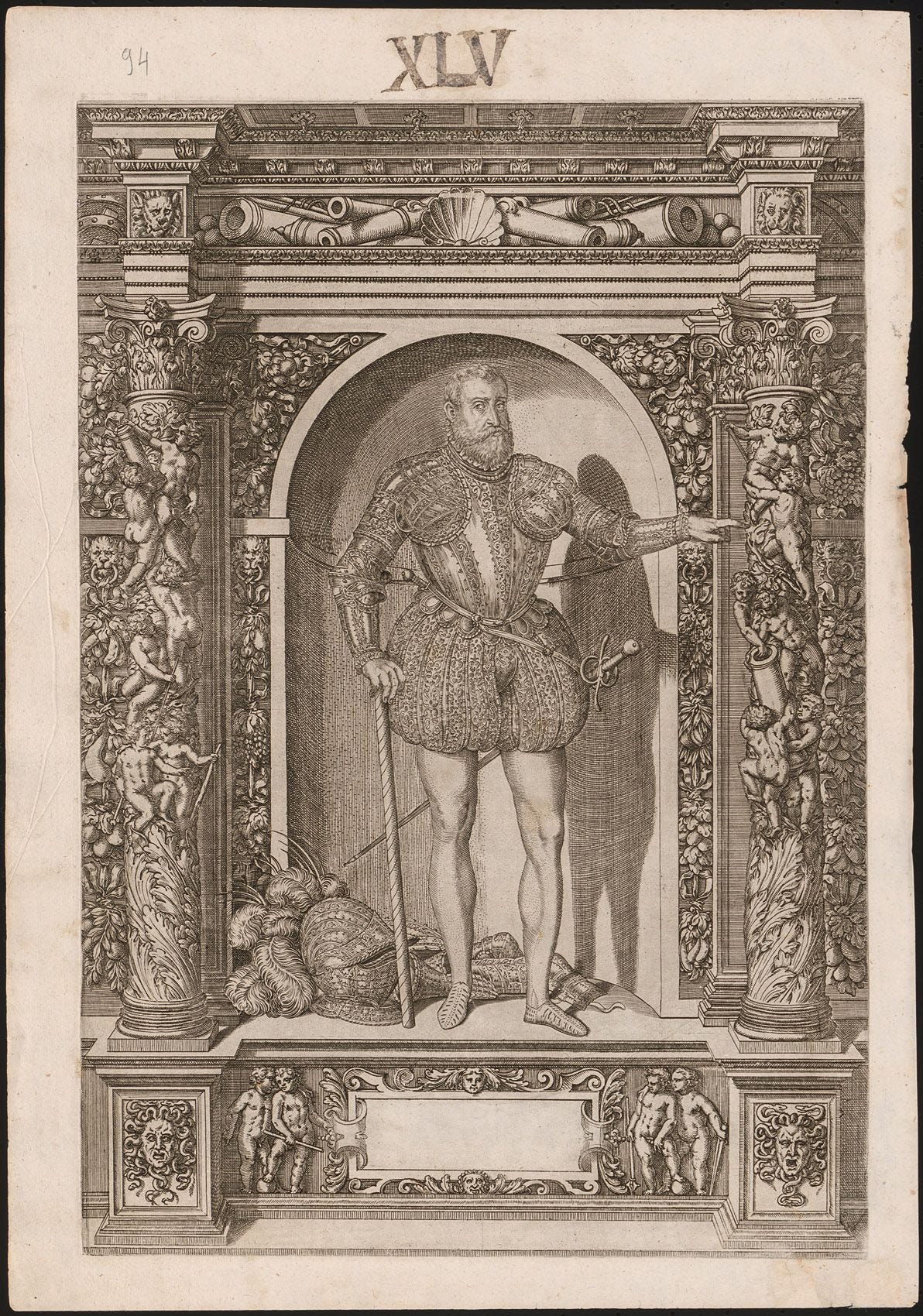

Figure 3

Armamentarium Heroicum, 1602. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Bibliothek, 81971

Figure 4

Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, c. 1560. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Schloss Ambras, GG 4711

Light Armor of Alfonso II d’Este (1533–1597), c. 1550–60. Northern Italy, Milan? Steel, etched with gold. Lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna, Inv. A 765

Figure 5

Andreas and Karl von Österreich, c. 1563. Kunsthistorisches Museum, GG 4711

Boy’s Armor of Andreas of Austria (1558–1600), c. 1568. Germany. Steel and leather. Lent by the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, Vienna, Inv. A 1497

[ad_2]

Source link